Comic Book Rarity: Who Cares?

I do. And, I think any collector worth their salt should care too. In this article I cover what rarity is, how books become rare, when it matters with respect to price, how to determine the rarity of your comic books, and a few final thoughts.

In part I’m writing this piece to raise awareness. Some sellers claim that comic books are rare when hundreds of thousands of copies exist. On the flip side, many naive collectors are drawn to the term “rare” like moths to a flame. They hit the buy button before doing any research and are burned in the process. Then other collectors are so numb to the overused term that they pay no attention to it. Let’s dive in.

What is rare?

According to Webster, rare is “seldom occurring or found: uncommon.” For comic books, the term has been used in various ways. Here are a few I’m aware of.

Absolute rarity has to do with a defined number of copies or a range of copies. For example, two titans of the hobby –Ernie Gerber and Bob Overstreet – contributed well known definitions based on the number of copies estimated to exist (from the Photo-Journal Guide to Comic Books Volume 1 and the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide 53, respectively):

Overstreet Definitions

Scarce = 20 - 100.

Rare = 10 - 20.

Very Rare = 1 - 10.

Gerber Scarcity Index (Explanations Abridged)

1 = Very Common. Can be found at virtually any store. No numbers provided.

2 = Common. Generally easy to find. No numbers provided.

3 = More than Average. Easier to find than a typical book from 1933 - 1960. No numbers provided.

4 = Average Scarcity. 1,000 to 2,000.

5 = Less than Average. 200 to 1,000.

6 = Uncommon. 50 - 200.

7 = Scarce. 21 - 50.

8 = Rare. 11 - 20.

9 = Very Rare. 6 - 10.

10 = Unique. Less than 5.

11 = Non-Existent but known to be published.

These notoriously strict assignments of rarity would disqualify almost any comic book of significance, including issues that are often called ultra-rare in the mainstream media. For example, Action Comics 1 (the first Superman) and Detective Comics 27 (the first Batman) are believed to have approximately 100 issues in existence, well above the Gerber and Overstreet rarity thresholds.

For me, I’m a little looser with my personal definition of rarity. I have no problem with someone saying a comic book is rare when there are fewer than 200 copies believed to exist, so Marvel Comics 1, Action 1, and Detective 27 would slide safely into the rarity pocket. One of the reasons I like the softer threshold is because it matches so well with the prevalence of comic books printed before and during WWII.

Relative rarity, as you might have guessed, refers to a comparison. What is the prevalence of one thing to another? You might hear someone say that golden age books (1938-1955) are rare compared to silver-age books (1956-1969). Or, you might hear someone say that Showcase Comics 4, the first appearance of silver-age Flash, is rare for a silver-age book.

Comparison of CGC Census Numbers for Action Comics 1 (1938), Showcase Comics 4 (1956), and X-Men 1 (1963).

Indeed, many golden age keys, like Action Comics 1, are 10, 50, or even 100 times rarer than silver-age keys. Likewise, Showcase Comics 4, while more prevalent than golden age comics, is several times rarer than most silver-age keys. Something you may have noticed is the relationship between rarity and the age of a book. You may have also noticed that I am using CGC census count numbers as a proxy for prevalence. We’ll come back to both topics in just a moment, but first let me talk about a few other uses of the word rarity.

Conditional rarity. That is, a book may not be rare overall, but it may be quite rare in top condition. A good example is Fantastic Four 1. While there are likely three or four thousand overall copies in existence, only three have been graded at a 9.2, three in a 9.4, and two in a 9.6, and none higher. Fantastic Four 1 is rare in high grade (i.e., conditionally rare).

Conditional Rarity: Fantastic Four 1 (1961) is rare in high Grade.

Even for modern books – with hundreds of thousands or even millions of copies in existence – conditional rarity can apply. For example, Spider-man 300 has over 37,000 copies graded by CGC overall, over 1,600 copies graded at a 9.8, but only 10 at a 9.9, and 0 at a 10.

Conditional Rarity: Amazing Spider-Man 300 (1988) is rare at 9.9 or higher.

Attribute rarity. This is similar to conditional rarity in the sense that it refers to a subset of a comic book issue. One example may be a common book with an unusual set of signatures. Cover variants and price variants can be lumped into attribute rarity. Other examples arise because of manufacturing errors. Venom 1 is not rare in and of itself. However, Venom 1 with the white cover printing error is exceptionally rare.

Attribute Rarity: Venom 1 (1993) is typically common but rare with the white cover printing error.

Market-availability rarity. The idea is that a book is rare if a copy for sale can’t be found on the market. The term was likely more applicable pre-Internet days when a buyer was limited to local shops, conventions, and mail-order catalogs. Today, very few books reach this threshold with so many books for sale being easy to search for via eBay and modern search engines. Nevertheless, there’s a high correlation between absolute rarity and the degree of availability in the market. For example, you will see X-men 1 for sale more than Showcase 4, and Showcase 4 for sale more than Action 1.

What are the factors that drive rarity?

In the most macro sense, there are two: Print run and attrition. The print run represents how many books were created. Attrition represents how many books were disposed of or destroyed over time.

Absolute rarity of a comic issue can arise from (1) a miniscule initial print run, (2) a high attrition rate, or (3) a combination of both. Gobbledygook 1, the predecessor of Teenage Mutant Ninja Comics 1 is a great example of a small print run: Supposedly only 50 were printed. It is believed that most of these copies have survived. Marvel Comics 1 is an example of absolute rarity due to severe attrition. Even though close to a million were originally printed, perhaps 100 exist today.

Gobbledygook 1 (1984) is rare due to a miniscule print run. Marvel 1 (1939) is rare due to extreme attrition.

How these two factors – print runs and attrition – contribute to absolute rarity differs dramatically depending on when a comic was printed. Many of the earliest books – in the ‘30s and early ‘40s – had huge print runs. However, the attrition rate was devastating. Let’s return to Marvel Comics 1. For every 10,000 printed, only one survives today. It’s hard for me to get my head around this jaw-dropping statistic.

Why did this happen? What transpired to reduce a million to a hundred?

The underlying cause was mindset. In the first three decades of comics books – the ‘30s through the ‘50s – virtually all people considered comic books as disposable entertainment. A common scenario probably looked like this:

Parent buys comic for child.

Child reads and handles recklessly.

Parent tosses comic in the trash.

The time between steps 2 and 3 varied. Sometimes a book was immediately thrown out. Sometimes it was trashed during spring cleaning. And, some were jettisoned when the kid moved out of the house. Further, many comics printed before or during World War II were consumed by paper drives to support the war effort. The danger didn’t stop there. During the 1940s and 1950s, many books were burned on moral grounds. And, remember, the normal risk of being thrown out as part of cleaning remained throughout.

By the 1960s, the world became a little less brutal for comics. At that point, the collector community emerged. A small but growing group began seeking back issues. Collecting had two profound effects: The survivability of comics began to increase and comics were handled more carefully.

By the 1990s, the cat was completely out of the bag with respect to comic books being collectors’ items. Publishers would hype comics relentlessly, doling out first issues of new series like PEZ candy. Speculators would buy dozens of the same issue hoping that in a few years their inked paper would turn to gold.

X-men 1 from the 1991 series set the record for the largest print run ever (over 8 million according to the Guinness World Records) and many collectors bought multiple copies.

A few decades back - in the ‘30s, ‘40s, or ‘50s – a kid might roll up a comic and stuff it in their back pocket. By the ‘90s, collectors were concerned about getting a fingerprint on their foil covers. Comics were as likely to be bagged and boarded as they were to be read.

Given this speculator-fueled circus, how does a modern book become rare? Certainly, comics published in the ‘80s through today survive at a high rate. So, for a book to be both modern and rare, they must be “born” that way. Or, in other words, the original print run must be incredibly small. Some of these small print runs happen innocently enough. For example, according to Heritage Auctions, Indy publisher Mirage Studios humbly photocopied 50 copies of Gobbledygook 1.

Other small print runs are due to something other than a small budget. Many big-name publishers know that collectors drool at rarity, so they manufacture it. They often do so by introducing variant covers in a print run, usually in some small proportion relative to the standard issue (e.g., a 1 in 100 variant).

According to Recalled Comics.com perhaps as few as 200 copies exist of the Amazing Spider-man 667 Dell’Otto Variant Cover (2011).

One of my favorite quotes is from Greg Holland regarding modern comics slabbed by CGC. In the Overstreet Price Guide 51 he says, “In the industry today, a regular edition (non-variant) with significant re-sale value seems to be more like a needle in a variant haystack.”

When does rarity matter with respect to price?

People have commented on my YouTube videos that rarity doesn’t matter. It's the demand that affects price. They will argue that many rare comic books aren’t worth much money.

I would ask collectors who hold the rarity-doesn’t-matter perspective to consider this: Just because some rare books aren’t valuable doesn’t mean that rarity isn’t correlated with value.

The argument is similar to saying that height doesn’t matter in basketball because some tall people can’t hoop. Of course height matters. Insert a little talent into a 7’ person and they have a good chance of making an NBA roster. Sure, there are a few NBA players under 6’ but they possess one-in-a-million talent.

Similarly, a little bit of demand can make an exceptionally rare comic valuable. On the other hand, it takes incredible demand for a common book to be worth money. For example, nice copies of Spawn 1 can sell for over $100 despite its abundance in high grade..

Because of high demand, Spawn 1 [1990] sells for over $100 in CGC 9.8 despite having over 16,000 in that grade.

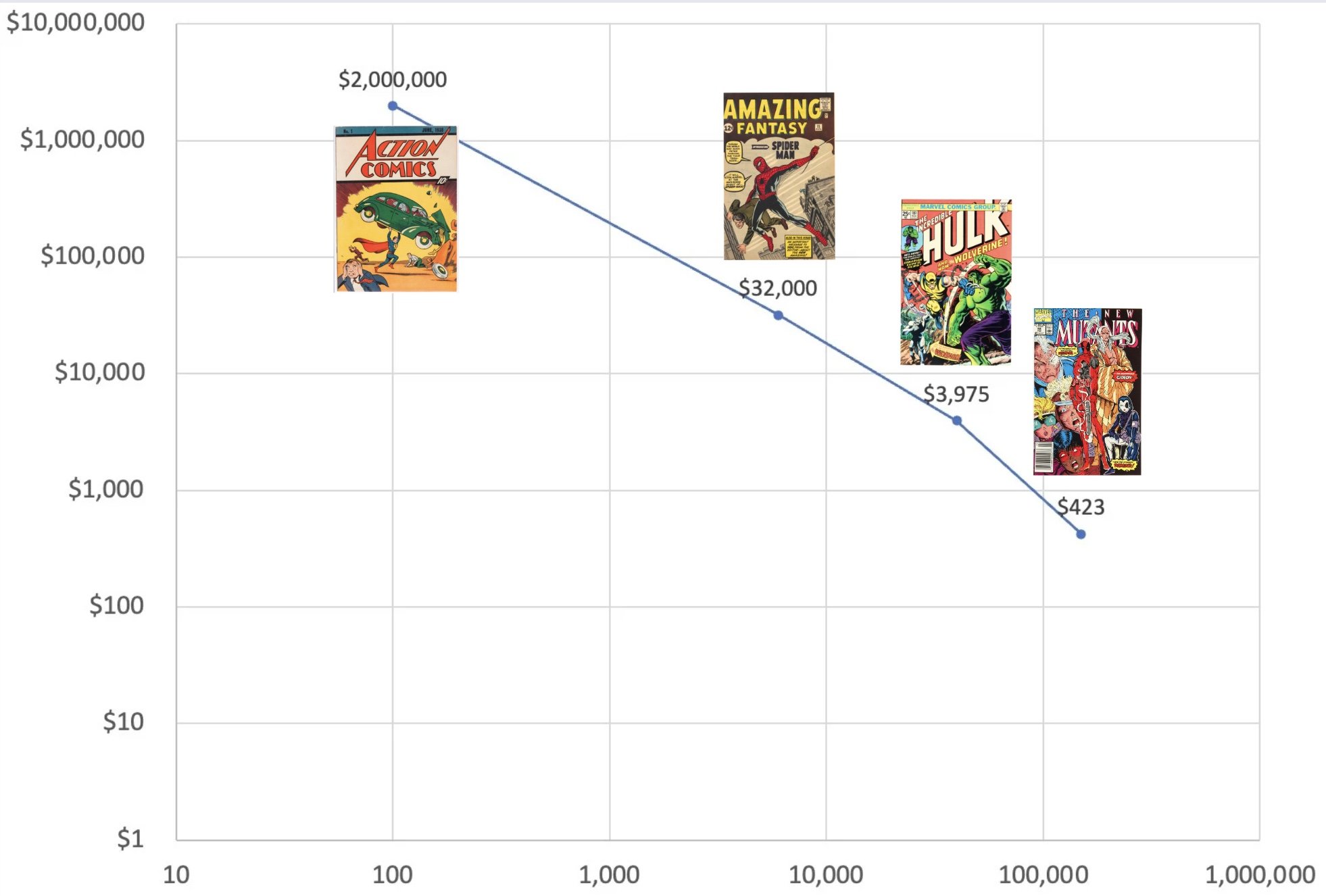

For the sake of a more apples-to-apples comparison, let’s take a look at several books with exceptionally high demand: New Mutants 98, Hulk 181, Amazing Fantasy 15, and Action 1. Each of these books are among the most popular – if not the most popular comic – in their respective ages. However, the median copy of each differs dramatically in price. Why? It’s because Hulk 181 is rarer than NM 98, AF15 is rarer than Hulk 181, and Action 1 is 50 times rarer than AF15.

Prices (for Median CGC Grade) vs. Prevalence of Uber-Popular Comic Books.

The point here is that for a book to be valuable it doesn’t have to be rare. However, it takes just a little interest in a rare book for prices to heat up. And, if a book is rare and in high demand, that’s when you see the price skyrocket to six and seven figures. On the other hand, it takes Deadpool-level fervor to dramatically boost the price of a common book to hundreds or thousands of dollars.

An important corollary to absolute rarity and price is something we mentioned earlier: Conditional rarity. While New Mutants 98 and Spawn 1 are easy to find in 9.8 or lower, they are much, much tougher to find in a 9.9 or 10. Consequently, the few books that do receive these nosebleed grades sell for many multiples of what a 9.8 typically fetches.

How do I know how many copies of a comic book exist today?

For most comic books, it’s difficult if not impossible to provide a precise number. There are so many comic books out in the world unaccounted for. The best we can do is provide a ballpark estimate.

Back in 1989, Ernst and Mary Gerber estimated the prevalence of every book in their Photo-Journal volumes, assigning each a number from their scarcity index. Certainly, the Gerbers had a sense of the relative rarity of comic books. For example, Amazing Fantasy 15 was given a rating of 4 (Average Scarcity, Between 1,000 - 2,000 copies) and Action 1 a 7 (Scarce, Between 21 - 50 copies). Nevertheless, the absolute estimates turned out to be too low for most books. CGC census reveals almost 4000 copies of Amazing Fantasy 15 and 81 for Action 1, which are certainly underestimates themselves of how many actual copies exist. Further, the most famous Gerber 9 (Very Rare) – Suspense Comics 3 – has over 40 copies on CGC census despite the Gerber’s estimate of only 6 to 10.

The Most Famous Gerber 9, Suspense Comics 3.

Since 1989 of course, we have the benefit of 35 years of additional collecting experience, the Internet, and the invention of the CGC census. Given that CGC has now been around for almost 25 years, its data can shed light on the prevalence of comic books.

In a recent interview, I asked CGC President Matt Nelson to explain the relationship between the CGC census and how many copies of comics actually exist. He acknowledged that the census serves as a better indicator of prevalence for high-value books. In other words, don’t get too excited when you discover only six copies of X-Factor 58 on the census. The book isn’t valuable enough to grade. There’s likely over one hundred thousand unaccounted for!

Nelson implied that CGC has graded between 50% to 80% of the most valuable books. And, by valuable he means books that are worth at least as much as Hulk 181, where it makes sense to grade copies even at very low grades. To that point, he estimates roughly 40,000 copies of Hulk 181 exist (currently just over 18,000 graded) and about 100 copies of Action 1 exist (currently 81 graded). Further, he estimates that most comic books printed before 1945 (i.e., before the end of World War II) have 50 to 100 copies in existence. A few notable exceptions being Batman 1 and Superman 1 that survive in multiple hundreds.

Matt also brought up a strategy to estimate prevalence: Benchmarking. That is if you were to look at Hulk 180, 181, 182, and 183; Hulk 181 has the highest CGC numbers. It’s likely not because 181s are more prevalent but simply because the issue is worth more, and thus more likely to be submitted for grading. Therefore, the Hulk 181 census numbers are better proxies of the surrounding issues than the adjacent issues’ respective CGC numbers are unto themselves.

For books from the 1980s forward, the CGC census is likely not that helpful to estimate existing copies. Even popular books with relatively high CGC census counts like the aforementioned Spawn 1 and New Mutants 98 are still not expensive enough to have good representation on the census. Instead, knowing the print run or sales figures can be more useful. By the way, print runs and sales figures are not the same as many comics that were printed were never sold. A resource that provides such statistics – although not universally for all comics – is Comichron.com. You can gain interesting insights from comics as far back as the 1960s.

Final Thoughts

I love exploring the concept of comic book rarity, largely because of its tie-in with history. The fact books from the ‘30s and ‘40s were so prevalent when created but so rare now is fascinating.

While not all rare comic books are valuable, rarity often plays a strong role in price. There’s a reason so many golden age comic books cost five, six, or seven figures. When you mix high demand with absolute rarity, prices explode. Further it is interesting how rarity intersects with the price of modern books, usually through conditional rarity or through attributional rarity.

What is the magic number of existing copies that represents the absolute rarity threshold? That is certainly up for debate. Legends like the Gerbers and Overstreet offered their numbers, which I think are a bit too strict. Nevertheless, in general, I agree that absolute rarity applies almost exclusively to comics printed before 1945.

And, to close, rarity is not the end-all-be-all of comic collecting. If you enjoy a comic, even if it is common, get it. However, if you are thinking of comics as an investment, be skeptical of when a seller uses the word rare. A little research goes a long way in differentiating a book that is genuinely difficult to find versus a book that is being pushed by hollow marketing.

I have created a few videos about rarity, if you would like to dig in.

Interview with Matt Nelson about Rarity: https://youtu.be/DdLPgcPTR0Y

An Overview of Rarity: https://youtu.be/IYbdbxuehl8

Rarest Golden Age Comics: https://youtu.be/0mxhhMs-pcE

Rarest Golden Age Grails: https://youtu.be/dOzUoWKIPm0

Rarest Silver Age Comics: https://youtu.be/PLAFev3tfYg

Rarest Bronze Age Comics: https://youtu.be/9TGgg_ShTUM

Acknowledgements:

Thanks to Ben Labonog, Greg Holland, and Matt Nelson for our conversations about rarity.

Images of comic books from Heritage Auctions (HA.com) except for the ASM 300, which is from CGC.com.